Fake news and misinformation have hit the headlines recently as concerns grow about its extent and impact. In this guest post, Dr Francis Young examines the parallels between contemporary digital fake news and English civil war newsbooks. Dr Young is a historian of early modern England and the Catholic Record Society’s Volumes Editor. You can follow him on twitter @SuffolkRecusant.

In the immediate aftermath of the US election, Facebook came under fire for allowing ‘fake news’ to dominate its platform, and there was much lamenting that traditional print media – which, in theory, at least tries to verifies sources and stories – has been replaced by social media as the source of ‘news’ for many people. The ‘fake news’ problem raises many profound and interesting questions about what ‘news’ really is, and what makes it ‘real’ as opposed to ‘fake’, but commentators have perhaps been too hasty in assuming  that fake news is something new and something alien to the ‘traditional print media’. In fact, the pattern of user-generated news that we see on contemporary social media platforms is closer to the original pattern of dissemination of news in the first age of print.

that fake news is something new and something alien to the ‘traditional print media’. In fact, the pattern of user-generated news that we see on contemporary social media platforms is closer to the original pattern of dissemination of news in the first age of print.

Defining what counts as ‘fake news’ is not straightforward, given the traditional print media’s overt political bias, spinning of rumours, wilful misinterpretation of statistical data, and editorial decisions to foreground minor stories and ignore many newsworthy ones. However, a strict definition of ‘fake news’ would exclude speculative stories that might be true and are supported by anonymous sources. The reporting of such stories with the implication that they are fact may be dubious journalism, but it is the longstanding practice of the tabloid press. ‘Fake news’, in the strict sense, would have to be the kind of story that no conventional newspaper or news website would run because it directly contradicts easily verifiable fact: for instance, the report that Donald Trump won the popular vote in the US election as well as the votes of the electoral college. No conventional media would run with a story that is demonstrably false; to do so would run the risk of being discredited as a news outlet or sullying the ‘brand’ of a conventional newspaper.

Fake news sites, especially those generated by user content, have no such scruples. Unlike conventional media, they do not exist in the hope of projecting bias onto readers, but are created solely for and by readers with a particular bias, who will share the stories (and thereby gain the sites advertising revenues) whether they are contradicted by demonstrable fact or not. Whilst some may realise that the news stories are fake, many others – enough to make ‘fake news’ sites a viable commercial proposition – rely solely on an ‘echo chamber’ of social media for all their news and may not even become aware that a story has been challenged.

The current news situation has striking parallels with mid-seventeenth-century England. In 1642, previously strict government regulation and censorship of printing collapsed as the War of the Three Kingdoms threw England’s central administration into chaos. As a result, more printed material was published in the year 1642 than in the entire preceding 165 years since William Caxton set up the first London printing press in 1476. One of the most popular printed genres that poured off the presses was the newsbook, a form closer in style to pre-Civil War one-off pamphlets than to later newspapers. Few if any newsbooks were periodicals in the true sense of being published on a regular schedule, partly because the chaos of war made regular publication difficult and partly because the newsbooks reported news as it came in rather than at fixed intervals. The absence of much editorial control of newsbooks and pamphlets meant that this material resembled today’s user-generated content. All that was required to create news was access to a printing press and the willingness of stationers (the Mark Zuckerbergs of the seventeenth century) to provide a platform for new printed material.

This, of course, the stationers did for exactly the same reason Facebook provides a platform for ‘fake news’ – because there was a commercial incentive to do so. The vast majority of stationers’ shops sold pamphlets, newsbooks and ballads in a small area of the City of London centred on St Paul’s Cathedral, although the establishment of an alternative Royalist capital at Oxford meant that newsbooks poured off the presses there as well. As might be expected in a divided nation, the newsbooks were highly polarised politically and rife with bias and unsubstantiated reporting of rumour as fact. The difficulties of verifying rumour as ‘news’ in an age of slow travel and poor roads are obvious, and this problem remained until the advent of the railways and the invention of the electronic telegraph in the mid-nineteenth century.

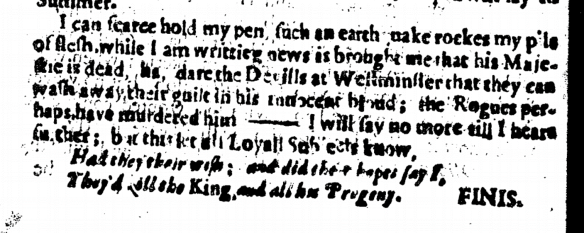

However, the newsbooks also crossed the line from exaggeration, rumour and bias into something more like ‘fake news’ by reporting victories as defeats and defeats as victories and by misreporting defections from one side to the other. In January 1643 The Kingdomes Weekly Intelligencer falsely reported the defection of the Royalist Captain John Fenwick, and in July 1644 the Royalist newssheet Mercurius Aulicus questioned reports of a Parliamentarian victory at Edgehill, implying a Royalist victory. In May 1648 Mercurius Bellicus even falsely reported that the king was dead. It is possible to excuse such reporting on the grounds that it was sometimes difficult to establish who won early modern battles – such as the indecisive Battle of Edgehill. However, the newsbooks were also able to report ‘fake news’ wilfully and deliberately because they could get away with, for the same reason today’s fake news sites can – because their existence was ephemeral rather than an established ‘brand’. Just as today’s fake news sites can simply rename themselves overnight, so seventeenth-century newsbooks came and went rapidly, with few names surviving more than a couple of years.

Mercurius Bellicus reports Charles I’s death…in 1648.

Anticipating the ‘viral’ user-generated content of today’s social media, seventeenth-century newsbooks often printed supposed personal letters describing events, many of which are demonstrably false. During the Revolution of 1688 a pamphlet circulated in the form of a letter describing a plot by Catholics to blow up the town of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk. An exhaustive search of the town’s surviving records reveals no hint that this was true, or even really suspected by the inhabitants. Yet then as now, marginalised minorities (in this case Catholics) whose voices were unlikely to be listened to were the targets of ‘fake news’. In mid-seventeenth-century England, as today in the UK and America, ideals of ‘objective’ reporting of news (which were perhaps always a fantasy) broke down seemingly irretrievably. So factionalised and polarised was society that fake news was acceptable to a large enough portion of the population to make it a recipe for commercial success.

References

The Kingdomes Weekly Intelligencer no. 5, 24-31 January 1642/3

Mercurius Aulicus, 7-13 July 1644

Mercurius Bellicus no. 16, 16 May 1648

A Copy of a LETTER out of the Country to one in London, discovering a Conspiracy of the Roman Catholics at St Edmund’s Bury in Suffolk, 30 November 1688, reprinted in F. Young, ‘”An Horrid Popish Plot”: The Failure of Catholic Aspirations in Bury St. Edmunds, 1685-88’, Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History 41 (2006), pp. 209-55, at pp. 223-4

Reblogged this on non sanz droict.

Hello,

I really enjoyed this blogpost, thanks so much for it!

This statement struck me: “As a result, more printed material was published in the year 1642 than in the entire preceding 165 years since William Caxton set up the first London printing press in 1476”. Impressive! May I ask where you got this information from?

Also, I was looking at the reports of some meetings of the Sforza privy council in the 1470s, and I found this: “fuit conclusum quod ille de Castigio, detentus quia vociferaverat mortuum esse Principem nostrum et Januam rebellatam, mittatur Papiam et ponatur in berlina, ut sit aliis exemplo”. So false news are a very early modern problem indeed!

Thanks for your comment, and for the Sforza example. The claim about the quantity of printed material in 1642 is derived from David Cressy’s analysis of ESTC titles

It was good to see this outline the parallels mentioned between the current state of affairs, and between what happened in the seventeenth century. It might be hoped that with so many people better-educated and better-outfitted for the drawing days, the trouble of “fake news” might be located to the backburner, given that while it might be a significant problem, it is no good sounding an alarm.

I saw this just as I was trying to figure out how to address the “Fake news” problem with my students in the European History survey course I’m teaching next semester, which starts in 1500. Thanks for giving me inspiration!

Pingback: Een afsluitende reflectie: is fake nieuws van alle tijden? | Katrien

There are numerous examples of traditional Media manipulating the narrative to further their own agenda and it doesn’t really matter where such news outlets are in the pecking order – gutter media or respectable journals they misreport events, ignore them, provide a biased commentary – the bar is set by traditional media. Before pointing the finger at those that up don’t ascribe to their standards now would be a good time for them to put their own houses in order. It’s no good pretending that you are on a distant Shore when there is no clear water between you.

Pingback: The Kings of Post-Truth | J D Davies

Pingback: What exactly is ‘fake history’? Some clarification | Francis Young

Pingback: Thursday Short: Alternative Media, Fake News, Radicals – Past and Present. | Radical! Political! Historical!

Pingback: Two Bens and a Mark: a talk at Ben Franklin Hall in Philadelphia | … My heart’s in Accra

Pingback: Fixing disinformation won't save us - Ethan Zuckerman

Pingback: “In other words, I think we’re trying to fix social media in part because it’s too hard and too scary to fix our political system” – “Fixing disinformation won’t save us” by @EthanZ – dropsafe

Pingback: Risk and Uncertainty – History Workshop

Pingback: Risk and Uncertainty – Women, Marriage and Law in Scotland