[In our mini-series ‘A Page in the Life’, each post briefly introduces a new writer and a single page from their manuscript.]

Laura Sangha

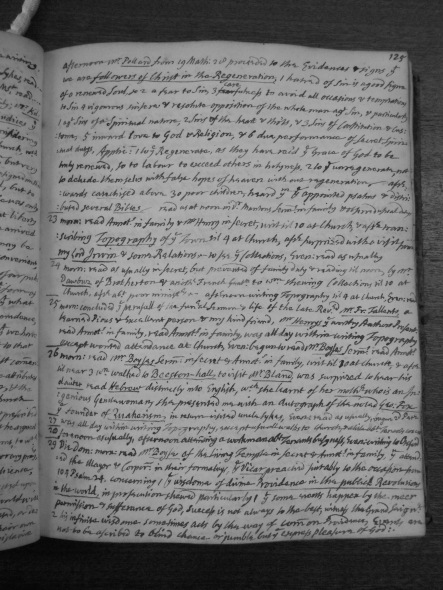

The Leeds antiquarian and pious diarist Ralph Thoresby (1658-1725) wrote a lot. An awful lot. Between the ages of nineteen and sixty-seven he kept a diary, often recording entries on most days of the week. Seven volumes of Thoresby’s life-writing survive, and at approximately 500 pages per volume that’s 3,500 pages of text. The page transcribed below is fairly typical at 550 words, so that makes close to two million words of Thoresby’s self-reflection out there. You don’t have to read them all though, because this page below provides a relatively good sense of the content and scope of Thoresby’s written self:

The Leeds antiquarian and pious diarist Ralph Thoresby (1658-1725) wrote a lot. An awful lot. Between the ages of nineteen and sixty-seven he kept a diary, often recording entries on most days of the week. Seven volumes of Thoresby’s life-writing survive, and at approximately 500 pages per volume that’s 3,500 pages of text. The page transcribed below is fairly typical at 550 words, so that makes close to two million words of Thoresby’s self-reflection out there. You don’t have to read them all though, because this page below provides a relatively good sense of the content and scope of Thoresby’s written self:

Brotherton Library, Yorkshire Archaeological Society MS 24.

[22 May 1709][1]

afternoon Mr Pollard from 19 Math:28 proceeded to the Evidences & signs that we are followers of Christ in the Regeneration, 1 hatred of sin is a good signe of a renewed Soul, so 2 a fear to Sin, 3 carefulness to avoid all occasions and temptations to Sin 4 vigorous sinsere & resolute opposition of the whole man against Sin, & particularly 1 against sins of a spiritual nature, 2 Sins of the heart and tho’ts, & 3 Sins of Constitution & Custome, 5 inward love to God & Religion, & 6 due performance of secret Spiritual dutys, Application: 1 to the Regenerate, as they have rec’d the Grace of God to be truly renewed, so to labour to exceed others in holiness, 2 to the unregenerate, not to delude themselves with false hopes of heaven with out regeneration – afterwards catechised above 30 poor children, heard them the appointed psalms & distributed several Bibles – Read as at noon in Dr. Mantons Sermons in family & observed usual duties

23 morn: read Annotations in family & Mr Henry in secret, writ til 10 at Church, & after transcribing Topography of the Town til 4 at Church, after surprized with a visit from my Lord Irwin & some Relations, to see the Collections, Even: read as usually

24 morn: read as usually in secret, but prevented of family duty & reading til noon, by Mr. Daubuz of Brotherton and another French Gentleman to whom shewing Collections til 10 at Church, after about poor ministers – afternoon writing Topography til 4 at Church, Even: read

25 morn: concluded the perusal of the funeral sermon & life of the late Revered Mr. Fr. Tallents, a learned Pious & excellent person & my kind friend, Mr Henrys the worthy Authors present. read Annotations in family, read Annotations in family, was all day within writing Topography except [wonted?] attendance at Church, Even: begun to read Mr. Boyses Sermon, read Annotations

26 morn: read Mr. Boyles Sermon in secret & Annotations in family, writ til 10 at Church, & after til near 3 when walked to Beeston-hall, to visit Mr. Bland, was surprised to hear his dau’ter read Hebrew distinctly into English, which she learnt of her mother who is an Ingenious Gentlewoman, she presented me with an autograph of the noted Geo:Fox the founder of Quakerism, in return visited uncle Sykes, Even: read as usually, begun 2nd Part

27: was all day within writing Topography, except usuall walks to Church, & a litle about Tenents concerns

28: forenoon as usually, afternoon attending a workman about Tenants busyness, Even: writing to Oxford

29 Die Dom: morn: read Mr. Boyse of the Living Temple in secret & Annotations in family, then attended the Mayor & Corporation in their [possibly formalriys], the Vicar preached suitably to the occasion from 104 Psalm 24. concerning 1 the wisdom of divine Providence in the publick Revolutions in the world, in prosecution shewed particularly 1 that some events happen by the meer permission & sufferance of God, success is not always to the best, witness the Grand Seigneur 2 his infinite wisdom sometimes acts by the way of common Providence, events are not to be ascribed to blind chance or jumble but the express pleasure of God:

It’s obvious that religion provides the organising framework for Thoresby’s diary. Almost half of the words here (225 at the start and end of the page) are actually notes on two sermons that Thoresby heard one week in May 1709, when he was fifty-one. Like a good grammar school boy he summarised the sermons’ doctrine and uses, diligently numbering each part. Elsewhere on the page, Thoresby kept a meticulous record of his daily religious regimen, listing those books that he used in ‘secret’, or private prayer (Joseph Boyse’s sermons, and probably Matthew Henry’s Exposition of the Old and New Testament), as well as those that were an aid when he led family prayer at the beginning and end of the day (Matthew Poole, Annotations upon the Holy Bible). We also learn about Thoresby’s daily visits to church, as well as his frequent ‘perusal’ of printed religious material.

St Johns Church, Leeds, in R. Thoresby, Ducatus Leodiensis (1715)

The content is therefore certainly representative of Thoresby’s chief aim in his life-writing, which was to keep track of his spiritual health and to monitor his journey towards salvation. In this, he is typical of many other early modern life-writers who were equally focused on recording and reflecting on their relationship with God. Thoresby was in fact a member of a community of non-conformist life-writers who circulated and shared their diaries, a process that provided them with exemplary models for life-writing and conventions which dictated the form, and to a certain extent even the content, of their writing. Thus Thoresby’s diary not only provides a window in the regular ‘lived experience’ of his own life, it also has the capacity to reveal wider strands of religiosity in contemporary culture.

Despite Thoresby’s self-confessed devotional aim in writing, this page also provides glimpses of other areas of his life. An extension of his religious duties can be seen in his involvement in charitable work. On 24 May Thoresby attended a meeting about how to support poor ministers. He also distributed Bibles for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, and on 22 May we see him testing whether poor children were worthy receivers by making them recite their catechism (a summary of the principles of Christian religion in the form of questions and answers) before him.

Thoresby was not only a peculiarly devout individual, he was also dedicated to topographical and antiquarian pursuits, through which he became acquainted with  many of the great and the good who shared his interests. Thoresby published the first history of Leeds in 1715: Ducatus Leodiensis: Or, the Topography of the Ancient and Populous Town and Parish of Leedes. It’s probable that the Ducatus is the manuscript ‘Topography’ he mentions working on here. Thoresby also amassed a very impressive collection of antiquities and curiosities in a museum attached to his Leeds house (including one of the most important coin collections of the day), and the collections drew a wide variety of visitors from all walks of life. It’s typical of Thoresby to grumble about the disruption to his routine when museum visitors drop in unexpectedly, as the clergyman Mr Daubuz and a ‘French Gentlemen’ do here, forcing Thoresby to delay family prayers until noon.

many of the great and the good who shared his interests. Thoresby published the first history of Leeds in 1715: Ducatus Leodiensis: Or, the Topography of the Ancient and Populous Town and Parish of Leedes. It’s probable that the Ducatus is the manuscript ‘Topography’ he mentions working on here. Thoresby also amassed a very impressive collection of antiquities and curiosities in a museum attached to his Leeds house (including one of the most important coin collections of the day), and the collections drew a wide variety of visitors from all walks of life. It’s typical of Thoresby to grumble about the disruption to his routine when museum visitors drop in unexpectedly, as the clergyman Mr Daubuz and a ‘French Gentlemen’ do here, forcing Thoresby to delay family prayers until noon.

Thoresby also wrote occasionally about ‘busyness’, particularly when it was proving problematic, and he was quite a prominent inhabitant in Leeds, despite his reluctance for public life. He served as a member of the Leeds Corporation for a time, and on 29 May we can see that he attended a formal occasion led by the Mayor. The passing nature of these comments probably reflects the low importance that they held in Thoresby’s estimation.

By the way, have you noticed just how neat Thoresby’s diary is? That’s because this a presentation copy of a diary, written up from notes every couple of days. The neatness of the text, the fact that there is only one crossed out word on the whole page, and perhaps the repeated phrase (‘read Annotations in family’) are all clues, but elsewhere Thoresby explicitly refers to writing up his diary. Incidentally, this page also serves as a warning of the dangers of early editions of primary sources. Thoresby’s diary was published in 2 volumes by Joseph Hunter in 1830, but nowhere does the edition mention that it is a substantially abridged version of the original[2]. Yet if we compare the page from Hunter with the original, it is immediately obvious that the editor has silently removed all the sermon notes, and much of the other devotional matter on this page. As a result of leaving out the material that is actually Thoresby’s chief focus, the 1830 edition of the diary has become something else entirely.

Evidently Thoresby’s diary provides a range of insight into individual and communal devotion, puritan religious cultures, life in provincial towns, and development of natural history and philosophy. Finally, it is brim-full of incidental detail that other sources often don’t provide. We see that in the early eighteenth-century, the epithet attached to the early Quaker George Fox could be ‘noted’, and that his autograph was sought out by collectors. More importantly, Elizabeth Bland, the Hebraist mentioned in the text, is only known to posterity through her connection with Thoresby – Elizabeth is mentioned in Hunter’s edition of the diary, and Thoresby requested that she write a phylactery in Hebrew for his Musaeum Thoresbianum (she presented a ‘Turkish commission’ to it as well). What and who else might we find in the other 2 million words…?

Want to know more? I have written other monster posts on Ralph Thoresby, and I have an article coming out later this year in Historical Research, focused on what Thoresby’s life-writing can tell us about his devotional life.

[1] Brotherton Library, Yorkshire Archaeological Society MS 24, p. 125.

[2] The Diary of Ralph Thoresby, ed. Joseph Hunter, 2 vols (London, 1830).

Pingback: A Page in the Life | the many-headed monster

Thanks for drawing attention to the layers of editing here: first the rough to ‘fine’ copy of the ms diary, then through the Victorian editorial machine to create a ‘modern’ printed edition. This process seems to be something that is both well known among historians but also not always considered when they scoop up their sources!

The role of piety here is also very interesting. Many of the mss I’ve looked at include material on sermon notes and some have introspective spiritual meditations as well, but I’ve noticed that there sometimes seems to be a process of compartmentalisation whereby the writers put their spiritual material in one volume (or section of a volume) and their ‘worldly’ material in another. But this doesn’t seem to be happening with Thoresby: he seems to discuss them both within the same chronological, day-by-day process. Did he have other ‘non-spiritual’ mss as well, or did he try to put his whole life into a single running diary?

Thanks Brodie. It’s hard to know exactly what Thoresby’s writing practices were – mainly the material that survies is his diaries and correspondence. There are many occasions in the diary when he does talk about writing that he is doing elsewhere though. He certainly had non-spiritual manuscripts relating to his intellectual pursuits, he made plenty of notes for his two books on Leeds, and we know he liked to copy engravings and lists of benefactors from churches when he was on his travels. He also spent a lot of time copying things out of other people’s MSS, as well as from printed books. My impression is that he wrote an awful lot, but that what survives is the much more organised and polished end of the spectrum.

Pingback: A Page in the Life of Thomas Parsons: Masculinity and the Lifecycle in a Stonemason’s Diary | the many-headed monster